Mars has a very different story to tell. Mars is also believed to have once harbored a global magnetic field generated by a dynamo in its core. Like Venus, its formation produced considerable internal heat energy as clumps of material and large asteroids bombarded the forming planet. Since Mars is smaller than Earth, it should have released its heat-of-formation, and cooled a lot faster than the Earth. If this is correct, Mars' core is likely to have fully solidified leaving no liquid metallic outer core to generate a field. Scientists can still see fossil evidence of a past global field in the form of surface magnetic field records measured by the MGS magnetometer (fig. X). These magnetic regions act like protective domes for the atmosphere, carrying magnetic fields similar in strength to the Earth's crustal magnetic field, about 1/10 the strength of Earth's main magnetic field. Outside these local magnetic domes, the Martian magnetic field is 100 to 1000 times weaker.

Observations of meteoric impacts (for example the Hellas and Argyre impact basins) that were created some four billion years ago show no evidence of a surface magnetic field. If the Martian field was operating back then, the surface in these basins would have re-magnetized as the material cooled. So, we can put a lower limit on when the Martian dynamo stopped functioning - about four billion years ago. Sometime between this age and 4.6 billion years ago when the solar system formed, Mars may have had an Earth-like magnetic field, which all but vanished 4 billion years ago.

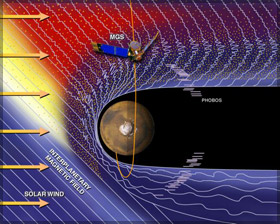

When scientists compare the locations of these magnetic regions with density maps of the Martian ionosphere, they line up very nicely. It appears that local magnetic fields can protect the ionosphere from erosion by the solar wind. In the same manner, Mars' global field probably once protected the Martian atmosphere from being carried off by the solar wind. Today, as ultraviolet light from the sun ionizes the gasses high up in the Martian atmosphere, the solar wind sweeps this ionized material away into space. Indeed, we see evidence for this from the Russian Phobos spacecraft observations indicating that Mars is losing thousands of tons of its atmosphere every year due to the direct impact of the solar wind on the atmosphere.

Figure 2 - The thin martian atmosphere coupled with the lack of a global magnetic field allow the solar wind to penetrate deep into the martian troposphere. It is now believed that the direct interaction between the solar wind and the martian atmosphere is partially responsible for the loss of water on the planet.

Observations from the Mars Global Surveyor (MGS) spacecraft show signs of erosion all across the surface of Mars. This erosion is usually attributed to the existence of flowing water on the surface. However, the vapor pressure for water is so low that any surface water should immediately vaporize in the rarified Martian atmosphere. So - Where did all the water go??? Most astronomers believe that Mars used to have a substantial atmosphere, and much warmer surface temperatures that supported global oceans of liquid water. So it would appear that the loss of a large portion of the Martian atmosphere, resulting in dramatic cooling of its surface and the disappearance of large reservoirs of surface water may have something to do with the loss of the Mars' protective magnetic field. Other scenarios for the loss of this ancient Earth-like atmosphere also include massive asteroid impacts, and a substantially higher solar wind density when Mars, and the Sun were still very young. Earth may also have lost its 'first' atmosphere in this way, but it was re-generated during subsequent volcanism. For Mars, with its rapidly cooling interior, volcanism was far less effective in rebuilding the atmosphere it had lost.